Henry was a remarkable man and a great educator. He passed away on April 6, 2011, but his legacy continues to live on. Here is his obituary in the Guardian.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2011/may/03/henry-pluckrose-obituary

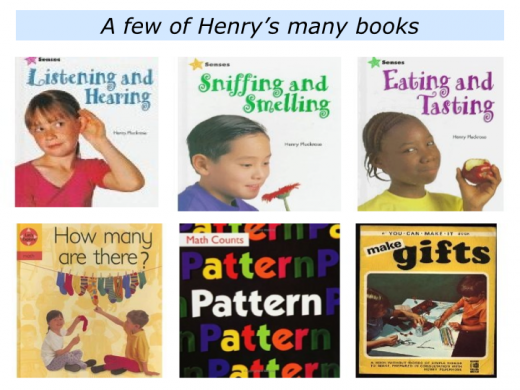

Try typing the name ‘Henry Pluckrose’ into a search engine. You will find he published over 300 books which, through a marriage of a simple text and photographs, encourage the development of thinking skills.

What the search will not reveal is the profound influence he had on primary education.

Henry was a remarkable teacher who inspired thousands of people around the world. Between 1968 and 1984 he was the head teacher of Prior Weston, a state primary school in London’s Barbican.

The school encouraged children to be creative. This was done through a curriculum which taught the key areas of literacy and numeracy, weaving them into every aspect of school life.

The results were impressive. It attracted a waiting list of students and hundreds of visitors from many countries.

I first heard about Prior Weston on the BBC radio programme The World At One. It was introduced as a school which ‘everybody liked’. Students and parents were so enthusiastic that the presenter pleaded:

“Please tell me one thing that is wrong with the school.”

Philosophy and Background

Prior Weston was successful because the staff believed in the educational – rather than engineering – approach to running a school. Whilst it was important to deliver certain results, these could be achieved by treating students as individuals.

For example, parents were asked to bring their child to school at least 12 times before the official starting date. Why? This was the child’s first introduction to an ‘institution’, so it was vital to get it right.

By visiting the school – and tasting different lessons at different times of the day – the child was more likely to feel safe, valued and excited about starting.

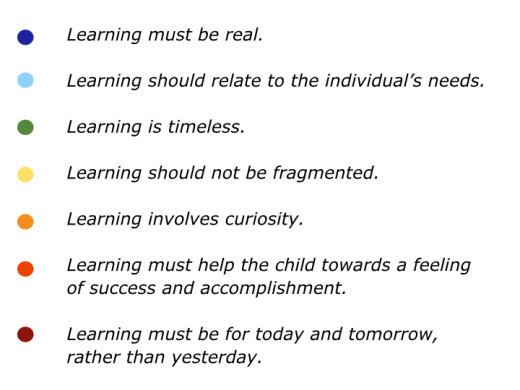

Writing in Open School, Open Society, Henry outlined some of the following principles about learning.

Prior Weston enabled children to master both social and educational skills. (Indeed, the second key statement on the prospectus emphasised the importance of social grace, that awareness and sensitivity for others should permeate school life.)

It also encouraged them to express their individuality through the arts – such as poetry, music and acting. Every year students went on scores of visits to local buildings, theatres, museums and work places. Here is a piece written by an eight-year-old after walking along a stormy beach.

A Storm

First it is calm, settled, innocent,

Then it gets unruly, restless, disturbed,

Then it is a monstrous giant, attacking, destroying,

Turning all its anger on the shore.

The waves grow bigger, fierce, more terrible,

Destroying everything in their path.

It is merciless, restless.

Boats overturned, people drowned, houses flooded.

It cares not for people dead,

It cares not for boats capsized.

It cares not for houses flooded.

It cares not.

Yet an hour afterwards, it is peaceful again,

Calm, settled, innocent.

Henry’s approach to education proved successful with students, parents and even governments. After writing Open School, Open Society, for example, he was invited to advise decision makers from many regions of the world. These included from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean and Eastern Europe, from North America to the Far East.

Visitors to Prior Weston were limited to 4,000 a year and, on one occasion, included the Queen of Denmark. The school encouraged children to build on their strengths, whilst also developing skills in other areas. Here is an old film about the school’s work.

https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-henry-pluckrose-1971-online

Henry called himself a ‘journey-man’ teacher, but others called him a genius. Certainly he was sought out by people who wanted to create enjoyable and effective educational systems. So let’s explore more about his background.

Growing up

Writing in his book of verse Word Shaping Tongue and Listening Ear, Henry explained:

“I was born in an impoverished district of South London in the early 1930s, late born of three children. My parents were working class and lived on a meagre weekly income.

“It must have been very difficult for them to allow my sisters to take the County Scholarships they had been awarded.

“The small annual sums granted them by the Council enabled them to accept a place in a Grammar School, where the course extended beyond the statutory learning age (14) when it would be usual for children from poorer families to leave school.

“Despite the pressure that this would have on their finances, the offer of places was accepted … perhaps because my mother resented the fact that her father had refused to allow her to accept a similar offer.”

Growing up in a tiny second floor flat, Henry learned from the homework brought home by his sisters. By the age of three he could recite swathes of poetry – such as passages from Hiawatha, poems by Wordsworth and whole tracts from the Bible.

Writing in 2008, he explained:

“I feel certain that all my writing is rooted in the first six years of my life, a time when I enjoyed the status of an only child and the added bonus of having the attention of three ‘mothers’ (his mother and two older sisters).

“During this time my sisters attended Greycoat Hospital School, Westminster. It must surely have been blessed by teachers who valued English in all its many forms, written and spoken.

“Each week Diana and Winifred (his sisters), a year apart in school years, were expected to learn by heart as homework, a specific piece of literature or poetry. It might be a psalm or Bible extract, a piece of prose or a poem.

“This involved much reading and reciting aloud in the only room available … the ‘living room/kitchen’ which all shared, a room featured in so many period novels.”

Learning, teaching and writing

After completing his National Service, Henry gained a teaching qualification from St. Mark and St. John College in Chelsea. From 1954 onwards he taught in several Inner London schools, building a reputation for enabling children to express themselves and develop their abilities.

During 1961 he met Frank Waters, editor in chief at Oldbourne Press, who had learned of Henry’s work on creative activities with children.

Frank asked him to produce a book on picture making. Published in 1962, this led to Henry creating many series of books for children, teachers and parents.

Books build reputations, which was the case with Henry. His approach was refreshing and produced results. People sought him out to understand the secrets of success.

Forever modest, Henry seemed surprised by the attention, but the students kept arriving. Roger Tingle was one of these people. He later wrote in the introduction of The Travels of a Journey-Man Teacher.

“In the spring of 1965, Henry was teaching on the very top floor of the John Ruskin School (in South London) and I joined him there as a student, a humble apprentice to a Master Sorcerer.

“His classroom was quite unlike anything I had ever visited before and his teaching methods unlike anything I had previously experienced.”

“The teaching space itself resembled an artist’s studio and was buzzing with a level of activity that only 42 lively ten and eleven year olds can generate.

“Whilst practical art and craft work was most clearly in evidence, it was the Arts in the broadest sense that formed the basis of the curriculum: drama, music, poetry and dance.”

“Particular importance was given to direct, personal experience. In practice, this meant that much of the children’s learning took place in a variety of settings outside the school: in museums, art galleries, churches and other historic buildings as well as the natural environment.”

Henry’s writings resulted in him receiving many invitations to lecture. He believed in course participants being active, rather than passive, so such assignments often turned into practical workshops for educators.

Rising through the ranks, he served as Deputy Head at the then experimental Eveline Lowe School in Bermondsey, before becoming Head of Prior Weston School in 1968.

Open School, Open Society

As mentioned previously, Prior Weston became increasingly well-known. Henry takes up the story in Travels of a Journey-Man Teacher:

“With a team of gifted teachers and supported by parents, we managed to create a school which was more community orientated than most of the schools in the area.

“So many visitors came to study our approach that after 5 years I felt a book would help clarify my thoughts as well as record something of the achievements of the teaching and support staff.”

He shared his thoughts with Audrey White, an editor he knew well, and it was agreed he should produce a book on open education. (Henry was not sure such a title would mean much to people.)

Evans Brothers published the book, now called Open School, Open Society, in 1975. Henry continues:

“Its theme was uncomplicated, reflecting how schools could become more open to the society they served. It looked at openness through a series of interrelated topics – a freer curriculum, child-centred learning, the role of the parent and teacher, the school as an important focal point in the life of the community.

“Its tenor was educationally left of centre, but it was liberal in tone and far from revolutionary.

“There was no reason – in my opinion then, nor in my opinion now – for it to make more than a small ripple in the educational pond. Instead, and to my astonishment, it created a whirlpool.”

Around the same time, a crew from Swedish Television were filming a 45 minute documentary at Prior Weston. So it was decided Open School should be published in that country to support the programme.

This led to Henry being invited to run workshops in Sweden and many other countries. He fitted these travels around weekends and holidays.

The publication of Open School neatly spans two other books of significance. Both stem from Henry’s fascination with History.

Let’s use the Locality (1971) examines ways in which young people can be shown how to interpret the past through the built environment in which they live. Children learning History (1991) published in English and Spanish, followed upon a research degree (M.Phil. London).

This was written after he had left Prior Weston in 1984 to become Head Teacher Fellow at Avery Hill (now the educational wing of the University of Greenwich).

During the 1980s Henry served on the Council for National Academic Awards and the Education Committee of The National Trust, The Royal Ballet and the Civic Trust.

In 1986 he joined the staff of the Royal Opera House, working part time in the Education Department, until finally retiring in 1999.

Poetry

During his later years he began writing poetry. (He wrote his first poem in 2003.) This was strongly influenced by another occurrence in his life. Henry takes up the story in Word Shaping Tongue and Listening Ear.

“Some eight years ago I was diagnosed as suffering from Parkinson’s disease, a neurological illness for which at present there is no cure.

“The illness slowly cramps the body, restricting movement making the simplest of tasks (like fastening a button) frustratingly difficult. Life eventually centres upon the support and dedication of those who are prepared to give their time to care.”

“Such restrictions I now suffer have brought with them an unexpected and welcome gain. Like W.H. Davies I have discovered the joy which comes from having time to ‘stand and stare’.

“To see for the first time beauty in a magpie’s plumage, note the deft skill of the spider as she weaves her web, watch the colours of the spectrum reveal themselves in floating dust when touched by a beam of sunlight.

“My attempts to put observations such as those into words (which some people may appreciate is a form of ‘play’) is an exploration of the way words fit together, while enjoying their sound pattern and cadence when spoken, their invasion of our emotions.”

“In a strange way my fascination with words returns me to my Lambeth childhood when I was submerged in literature and poetry … irrespective of its appropriateness to my age or understanding.

“Like many a working class child I welcomed ‘the hand-me-downs’ of my older siblings.

“There was one small difference. My sisters did not give me clothes which no longer fitted, their hand-me-downs were more ephemeral and longer lasting, a love of words.”

Here is one of the poems from his book.

When you speak

When you speak, speak gently,

in the gentleness lies healing.

When you speak, speak thoughtfully,

impetuous words bring pain.

When you speak, be restrained.

Self promotion is demeaning.

When you speak, speak truthfully,

lies corrupt present and future.

When you speak tell of what might be,

the past is a graveyard of unfulfilled ambition.

When you speak, speak with love,

love transcends self, blessing giver and receiver.

In the speech let moments of silence dwell.

For in silence there is meaning.

Principles

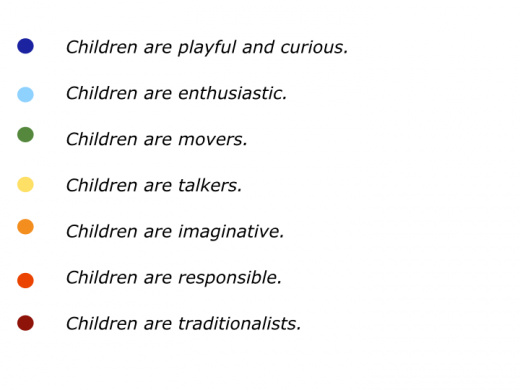

Henry based his educational approach on certain principles. Let’s explore some of these that enriched the lives of children, schools and their local communities.

Schools must be based on how children learn

Sounds commonsense? Of course, but it is amazing how many nations forego such basic ideas. Writing in Open School, Open Society, Henry explained:

“The school, it has been said, needs to fit the child. By implication this suggests that teachers, students, parents, administrators and members of our education committees have really thought about the nature of the young child. Can it be otherwise?

“Unfortunately – yes … So let us look briefly at the child from the ages of 5 to 11, for it is upon his particular qualities (physical, emotional, intellectual and social) that the primary school should be built …”

Children are playful

Children learn through play. But play sometimes gets a bad press, as if it has nothing to do with growth, says Henry.

As thinkers such as Pestalozzi, Froebel and Montessori have pointed out, however, there is nothing as serious as play. Doing the things we find fascinating leads to what today is commonly called a sense of flow.

We flow, focus, finish and, as a result, gain a sense of fulfilment. Peak performers go through this process all the time. Prior Weston enabled children to follow this path and do creative work.

Children are curious

The early years of most children are spent in looking, testing, probing, querying, believed Henry.

He said: “The teacher’s task is to take this curiosity and, by creating situations and providing materials which are themselves stimulating, use it to help children towards a better understanding of the world.”

Children are movers

Children come to terms with the world through their bodies and senses, said Henry. They explore through sight, sound, taste, touch and smell. Schools should therefore be designed – and a curriculum followed – in ways that enable children to move, explore and make sense of their experience.

Children are talkers

Children love words. They love the sounds words make, said Henry, and the response these evoke from the adults in their world.

Henry loved listening to his sisters recite poems and hearing words that stretched his imagination. Such words present challenges. The child longs to understand and extend his personal vocabulary. (At five years of age, children assimilate 5 new words a week.)

Children are enthusiastic

Children are full of energy. Providing their basic needs are met, life is fun. The world is there to explore and every day is different.

Henry said: “What we need to do is harness the children’s own enthusiasms to the subject areas which we might wish them to consider. Once a child is personally involved, learning follows.”

Children are imaginative

There is an old story about two candidates being interviewed for the role of leading a start-up business. Person A had a high IQ, having passed many exams; Person B had a relatively low IQ, but he had built his own company.

Pointing at a nearby chair, the interviewer asked each person:

“How would you use that chair to build a business?”

Person A gave a few answers. Person B immediately produced a flow of ideas. Some were mad cap, but some would make money. The interviewer wanted to differentiate between conventional ‘intelligence’ and creative imagination.

Prior Weston employed many vehicles – such as project work, theatre, music, dance, painting and field trips – to stimulate children’s imagination and help them to solve problems.

It was important to help children to recognise that throughout their school days, and their adult lives, they will meet problems which they will need to solve.

Children are responsible

I visited Prior Weston in the early 1980s. The children hosted visitors, looked after the library, led the daily assembly, helped younger pupils at lunchtime and behaved responsibly.

Responding to high expectations, they took a pride in helping to run their school.

Children are traditionalists

“Children like to have a routine of living within the school that they can understand, a pattern they can follow,” said Henry.

“‘We always …’ does not have to relate to the PE lesson every Tuesday at 10.30. ‘We always …’ should relate to attitudes, the way in which a child relates to child, teacher to child, child to teacher.

“Consistency of approach, consistency in care, consistency in understanding is what young people demand.”

Great educators provide the security and stimulation that enables students to grow. This leads to another key principle in education.

School can enable children to develop

their abilities and achieve a sense of success

Let’s return to some of the points Henry made earlier. Learning involves curiosity; learning involves problem solving; learning can lead towards a feeling of accomplishment.

How to translate these themes into action? Writing in The Caring Classroom, Henry gave an overview of two approaches.

Prior Weston’s teachers gave children the opportunity to use what today are called multiple intelligences.

They enabled students to build on their strengths; to pursue their chosen learning styles; to delve deeply into a subject; to see connections across topics, such as architecture, maths, language, aspects of daily life; to produce visible products, such as essays, poems, drawings or photographs.

These products could then be displayed around the school.

School can become an

integral part of the community

Henry stressed the need for schools to bring learning to life by going out into the local community. During foreign trips he was frequently reminded that Prior Weston was fortunate to be surrounded by museums and art galleries in Central London.

Certainly this was the case but, on the other hand, Henry often ran workshops in towns where there were many learning resources in the local community.

These included, for example, factories, mines, ruins, theatres, old people’s homes, canals, graveyards, farms, power stations and other amenities. Children could visit these places, experience the environments and produce creative work.

Writing more than 30 years ago, Henry also envisaged the school becoming more integrated into the community. His ideas included:

The school as a learning centre

This included acting as an adult learning centre – possibly where older people could pass on their skills to younger people; a holiday play centre; a meeting place for the local tenants association; a centre for community leisure activities – such as art, photography and dancing; a technological resource, providing computing and other facilities.

Many of these ideas have now been translated into action.

The school as a community support centre

Henry wrote that many problems were brought to him. These included: a girl in trouble with the police; a mother requesting help in regaining custody of her son; a sudden death of a parent; the side-effects of a complex divorce; a badly beaten child and a family coping with rent-arrears.

Whilst not always able to provide expert advice, the school staff created support structures for helping parents and children to deal with problems. Henry saw the future school as playing a key role in helping people to deal with such difficulties.

The school as a pioneering institution

School could create links across the local community. Certainly it could reach out to other learning centres, social projects and work places.

But what about bringing work places into the school? How would forty-five year olds react to experiencing the ways young people learn today?

Henry suggests, for example, involving parents in their children’s education. Writing in The Caring Classroom, he explains how this could be translated into action.

When working in a Swedish school with a mixed aged group of 7 – 13 year old children, he invited the pupils to provide evidence of the history of themselves and their families. He writes:

“Within 24 hours the classroom was awash with ‘treasures’ … baby clothes and toys, photographs of parents and grandparents, holiday snapshots and a wide range of objects which had particular significance for the family from which they had come.

“When parents visited the classroom, their display of collective pasts provoked intense and purposeful discussion.

‘Who would have thought’, said one father to another, ‘that we both still own the toy bears we had as toddlers!’ ‘Isn’t it interesting’, was the response, ‘that modern bears don’t look like ours.’

“Such a conversation points to something more than nostalgia for a shared past. It indicates a way in which teacher, parent and child can be drawn together through a project and experience shared.”

Practice

So what have been the effects of Henry’s work? During the past 40 years many generations have learned from his books. Thousands of teachers have been inspired to create environments that have enabled children to develop.

Many primary schools have integrated his ideas into their daily lives. The ‘educational’ approach he believes in has, of course, often been faced by the ‘engineering’ approach led by administrators. Nevertheless, Henry’s work continues to educate the heart, head and hands.

Writing about The Travels of a Journey-Man Teacher, Roger Tingle says:

“The only argument I have is with the title of this book. Having had the rare privilege of working alongside Henry for so many years, I believe that this teacher will be remembered not as a journey-man but as a genius.”

Looking back at Henry’s work, it is interesting to see what he wrote more than 30 years ago about the future of schools.

Along with giants such as Froebel, Montessori and Dewey, Henry has shown how to translate real education into action. He has enabled many people to live more fulfilling lives.

Leave a Reply