Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi was a Swiss educator and social reformer who had a profound influence on education.

Living between 1746 and 1827, he created several educational communities and also wrote popular books, such as How Gertrude Teaches Her Children.

His ideas spread across the world, influencing people such as Friedrich Froebel, the inventor of the Kindergarten.

Heinrich – as he was known – believed the purpose of education was to help people to fulfil their potential and reach what he called their moral state. They would then be more able to help others and give their best to the world.

Philosophy and Background

Pestalozzi produced many books and letters. Different people take different things from his work.

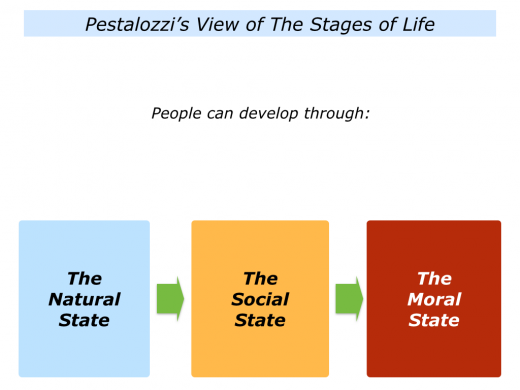

Some know his views on human development: that people go through certain stages in life – the natural, social and moral stages.

Some know his views on learning: that people first learn through their senses – first the experience, then the word. Some know his views on social reform: that people must be given the opportunity to use their talents.

Some know his views on educators: that teachers must embody love in order to enable their students to learn.

Some know his views that real learning only comes through action. For example, if you want to learn about generosity, you can only do it by actually practicing generosity.

Heinrich wrote on many topics. But in this article we will focus on those themes that relate to people and their strengths. These include:

People go through three states to fulfil their potential. They develop through the natural state, social state and moral state.

People have inner powers that can develop by learning through the heart, head and hands.

People learn best if their teachers embody love. They are then more likely to develop in a state of composure.

People learn through the senses: first the experience, then the word.

People can only develop their inner powers by action. They are then more likely to reach the moral state.

You can discover much more about Heinrich’s work at several web sites. These include:

The Pestalozzi-Fröbel-Haus

Founded in 1874 by Henriette Schrader-Breymann, a student of Friedrich Froebel, this has a long tradition of educating teachers. You can find it at:

Pestalozzi World.

Backed by, amongst others, The Dalai Lama, this organisation employs the Pestalozzi approach to help children across the world. You can find it at:

Heinrich Pestalozzi

Perhaps the most comprehensive site, however, is run by Professor Dr. Gerhard Kuhlemann and Dr. Arthur Brühlmeier. This provides a massive resource of background and ideas relating to Pestalozzi.

Dr Brühlmeier also has a separate site that offers more information. Both are well-worth visiting. You can find these sites at:

Pestalozzi had a great influence on education, but for many people he remains an unknown figure. So let’s explore his life and work.

Beginnings

Heinrich was born in Zurich in January 1746. His parents experienced many swings of fortune during their lives together.

For example, during the first 8 years of their marriage they had seven children, but only three survived. Heinrich’s father, Johann Baptist Pestalozzi, found it hard to provide for the family, whose circumstances deteriorated further when he died in 1751.

On his death bed, however, he implored the family’s servant, Babeli, to care for his wife. She stayed with the family, often without pay, for many years.

Despite extensive research, finding the name of Heinrich’s mother has proved extremely elusive. This is interesting, especially as he later wrote much about the importance of a mother in child development.

Heinrich received lots of love from his mother and Babeli, but he led a somewhat sheltered life. He also remembered being criticised for his clumsiness, writing:

“I totally lacked the ordinary and everyday experiences by which most of the children – by tackling and solving thousands of tasks – can be taught and prepared for usual skills of life, almost without them knowing or wanting it.

“In my nursery there was almost nothing to keep me busy in an instructive and reasonable way and I, being very lively, usually ended up with destroying everything I got hold of, without wanting to, so one thought it best to give me as little as possible to occupy myself with, so that I would only destroy as little as possible.

“‘Can’t you sit still at all? Can’t you keep your hands still at all?’ These were the words I had to hear permanently.

“I was not a person to sit still, I could not keep my hands still and the more I should do so the less I could. If I did not find anything else I took a cord and twisted it until it did not look like a cord any longer.

“Every leaf, every flower that I happened to get hold of had the same fate. Imagine a mechanism and its motive force which someone tries to stop violently.

“This force of the wheels turning against the hindrance is just the picture of the influences of my conditions on the direction of my forces striving for development and occupation.

“The more they were checked the more confused and violent they got whenever they wanted or were able to show.”

Influences

Heinrich was teased at school – partly because of his appearance, partly because of his clumsiness. He was determined to learn, however, and attended virtually every school in Zurich.

“This thirst for knowledge increased as he got older. Writing about Pestalozzi’s education, Arthur Brühlmeier explains:

“The schools that he attended included the minster’s ‘Schola Carolina’ and the ‘Collegium Carolinum’.

“The latter school was similar to a college, and it was the teachers here who suggested that Zurich (or Switzerland) was undergoing an ‘Age of Enlightenment’ – a time of learning, exploration and change.

“Pestalozzi initially wanted to become a pastor like his grandfather. However, for unknown reasons he studied law instead. His favourite teacher was Johann Jakob Bodmer (1698-1783); a teacher who was well-known even outside Zurich and Switzerland, and who always had a large following of talented students.

“Johann Jakob Bodmer and his students formed a group called ‘Helvetische Gesellschaft zur Gerwe’ or ‘Patrioten’ for short.

“They met in a room owned by the guild of the tanners, and discussed the thoughts of ancient and modern philosophers. They also published their own magazine called ‘Erinnerer’.

“Philosophers that were discussed included Plato, Titus, Livius, Sallust, Cicero, Comenius, Machiavelli, Leibnitz, Montesquieu, Sulzer, Hume, Shaftesbury and Lessing. However, above all, Jean-Jacques Rousseau was the main philosopher of interest.

“Through their weekly meetings, the ‘Patrioten’ spoke out against the powerful ruling class and the government reacted nervously … (Pestalozzi) believed in righteous morals and pushed strongly for law reform within the state.

“He wanted to see the replacement of an unjust government, characterised by a separation of power, with one that believed in equality.

“He was also passionate about ending the obvious exploitation of the landscape and its inhabitants.

“Unfortunately, Pestalozzi became notorious within the town and this destroyed his prospects of a public position, when in principle, this should have been available for him as a town citizen.”

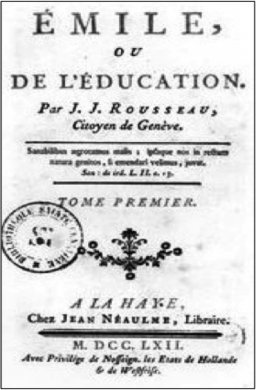

Rousseau’s books, such as Emile, had a strong influence on Pestalozzi, who later put such philosophies into practice, often with mixed results.

Emile is described as a work of ‘semi-fiction’ and outlines Rousseau’s philosophy of education. The narrator is the tutor, who describes the education of his student, Emile.

Rousseau believed that human beings were naturally good, whilst many institutions were corrupt. It was therefore good to educate the child away from bad influences in society. The ideal place would be in the country, where they could also learn from nature.

Emile explores how Rousseau’s themes applied to education. These included:

Children should be encouraged to follow their natural curiosity.

The teacher should be a guide or facilitator. They should enable – rather than interfere with – the child’s natural growth.

Human beings go through different stages in their lives.

Children should be encouraged to enjoy their childhood, rather than expected to be little adults. It is important to cultivate these childhood experiences.

Education should be connected to real life.

It should be based on the child’s daily experiences, take place in the real world and also involve the parents.

Education should also help children to learn morality.

They must be encouraged to follow their own nature, but also respect other people. This is vital in order to enable them to develop and live a righteous life.

Heinrich admired Rousseau, but he had difficulty reconciling enabling children to be free with the need to create social order. Later we will explore how he tried to translate these ideals into practice. Before then, however, let’s consider other aspects of his personal life.

Marriage

Heinrich was 21 when he fell in love with Anna Schulthess, who was then 29 years old. They met in 1767 at the funeral of a mutual friend. Feeling consumed by love, he expressed these feelings in one of his first letters to her. He wrote:

“Mademoiselle! In vain I am searching my calmness again … I dared to look at you in astonishment, to talk to you, to write to you, to think, to feel, to tell you your own personal feelings.

“I should have known my heart’s weakness and evade such dangers where all hopes are vanishing.

“What shall I do now, shall I be silent and be consumed with silent grief, not speak and expect no hope and relief from my misery? No! I do not want to be silent.

“The whole day I am only thinking of you, of every word you said, of every place where I saw you … My high respect for you turned into a huge passion of love. Every day, every hour, every moment it is increasing … “

You can find much more about Anna and Heinrich’s relationship at the Heinrich Pestalozzi site. Here is the link:

Heinrich and Anna were quite different. Physically he was considered ‘plain’; whilst she was seen as a beauty. He was relatively poor; she came from a prosperous family.

He was an idealist, with a burning desire to improve the world: she was more grounded. He expressed his feelings for her immediately; she was cool at first, warming to him later.

Anna’s parents disapproved of the match, so the couple met secretly, before eventually marrying in 1769. They had a son, Jean Jacques, who Heinrich tried to raise following Rousseau’s principles.

Unfortunately Jean Jacques suffered from epilepsy and several ailments. These contributed to him failing to fulfil his father’s hopes and he died aged 31.

Anna supported Heinrich throughout his various ventures. Her relatives actually provided money to care for the family after some projects collapsed.

Discovering his vocation

– educating the poor

Heinrich longed to live ‘the natural life’ in the country, so his first venture was as a farmer at Neuhof. He began by experimenting with conventional farming, cotton weaving and other activities.

Despite seeing himself as an entrepreneur, Pestalozzi had little practical business sense or, for that matter, feeling for agriculture. According to the Heinrich Pestalozzi site, however, this helped to give birth to his true vocation – educating the poor. The site says:

“Although Pestalozzi’s cotton business was not at all successful it initiated the change of the Neuhof estate into a house for the poor.

“Pestalozzi saw hundreds of children that lived in misery, were neglected and forced to beg and he realized that he was only able to help them, when they learned to work, when they were educated and when they learned spinning, weaving or intensive agriculture during the social situation at that time.

“So he started to bring poor children to his house about the year 1773. He fed them, he gave clothes to them, showed them how to work, taught and educated them. And so during the year 1774 his farm changed step by step into a house for the poor.

“He wanted to create a practical environment in connecting agriculture and developing industrial work to prepare poor children for a life, where they were able to overcome their poverty by their own forces.

“In 1776 twenty-two children lived in Pestalozzi’s house, two years later there were already 37.

“He built two new buildings – a factory room and a children’s house – and employed learned weavers, spinners and farm lasses for the work in the fields who should supervise the children during their work.

“While the children were working at the spinning-wheel or at the loom Pestalozzi taught them reading or arithmetic. The whole life at the Neuhof was filled by Pestalozzi’s intention to warm the children’s hearts for a decent life in truth and love.”

The Neuhof experiment ended in financial failure, but Heinrich’s work caught the eye of Isaak Iselin, an official in Basel, who encouraged him to write about his philosophy and practice.

Writings

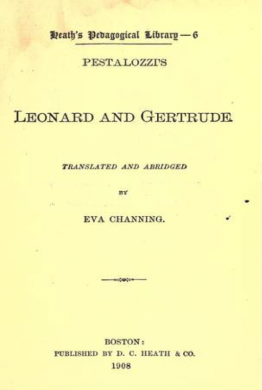

Pestalozzi’s first best-seller was Leonard and Gertrude. Written in the form of a novel, it begins by describing how Leonard’s drinking and debts bring difficulties to the family.

Gertrude, his wife, then translates her love into action and, in the process, transforms her family and the local community. The Pestalozzi World website describes some of the events that surrounded the publication of the books.

“His book Leonard and Gertrude achieved such a success that his old supporters came to appreciate his qualities again. The Agricultural Society of Bern gave him a gold medal, which he sold almost immediately.

“The success of the book depended on factors which were much less evident in later works of the same kind – the interest and humanity of the story, the drama, the humour and the character drawing.

“The moralising and the propaganda on behalf of education were but incidental and subsidiary, though nevertheless extremely impressive and significant because the presentation was so skilful.

“Gertrude’s efforts on behalf of her weak-willed husband, her influence in village life, her careful training of her children – all these threads of the story contributed towards the educative element in an entertaining novel.

“In addition, however, they offered to the discerning reader a complete picture of the writer’s concept of the true function of education.

“The author was saying, in effect, that ordinary life can be used to educate – that a school should provide the same companionship and duties as a good working-class home.

“He was emphasising that the development of the individual and that of the group are bound up together – that the individual can grow in mind and spirit only within a social setting, that a child needs help and guidance in obtaining the fullest intellectual and spiritual benefits from experience.

“He depicted Gertrude as the perfect working-class housewife, fulfilling her natural function as the first teacher of her children, training them through their senses, guiding their observations of nature and drawing them into work-activities contributing to the family’s welfare.

“Through her example, the leader of the village came to realise that the proper education of the child was the only way of bringing about reform and improvement, and a village school was set up on lines in harmony with home education.

“Pestalozzi aimed to show how education should be an integral part of community life, and also how both Church and government should co-operate in the forwarding of this major social service.”

Leonard and Gertrude was translated into many languages and made Pestalozzi’s reputation. You can read an excerpt from Google Books at the link below.

Heinrich followed up with several other papers and books, before publishing another best-seller How Gertrude Teaches Her Children. This was actually an outline of Pestalozzi’s views on education, rather than a continuation of the Gertrude story.

Written in the form of letters, he explained that schools should provide a secure environment. They should help children to learn through the senses and enable them to find useful vocations.

The book also describes the concept of Anschauung, for which there is no direct translation of this word into English. But it involves learning through sense impressions: first the experience, then the word. Pestalozzi’s books spread his reputation and helped him to secure future work.

Recognition

Heinrich spent the rest of his life translating his ideas into action. The first opportunity came at Stans. After French troops invaded the Swiss confederation 1798, Pestalozzi offered to care for children in an orphanage.

His work was curtailed in 1799, however, when the French military re-commandeered the building and turned it into a hospital. Despite this setback, the experience proved invaluable. The Heinrich Pestalozzi site explains:

“The stay in Stans leads to the decisive change in Pestalozzi’s life. From now on he wants to become a teacher and soon he gets this possibility in Burgdorf.

“A short time afterwards he is able to realise his idea of an approved school connected with an institute for in-service training of teachers.

“He gains the support of the Helvetic Government, is able to engage several competent colleagues and wants to develop his new kind of giving lessons.

“The fundamental writing for that ‘Wie Gertrud ihre Kinder lehrt’ makes Pestalozzi famous as a great educator and renewer of the ‘Volksschule’ and his visitors come from all over Europe to Burgdorf.

“Pestalozzi gave all his energy into finding a method to teach the pupils in a natural, more spiritual way. He put away all school- books and let the children experience their physical surroundings with all their senses.

“Learning, he believed, is predominantly about thinking first, then reading. After eight months his pupils took an examination and the success rate was so high that he was entrusted with one of the higher boys school in town.”

Explaining that Pestalozzi was then able to create a teaching centre at Yverdon, the site continues:

“Pestalozzi’s institute in Yverdon quickly gets famous and his pedagogical impulse dwells on all over Europe but above all on Germany and especially on Prussia. Numerous visitors come to Yverdon to visit the institute.

“The actual hey-day were the few years from 1807 till 1809, perhaps the years till 1815. Economical difficulties and bitter arguments lasting for years between the employees finally ruin the institute, which Pestalozzi is forced to close down in 1825.”

The final years

Heinrich kept returning to his vocation. At the peak of his fame at Yverdon, he wrote to a colleague:

“What I have here is not what I want: I was looking for a home for poor children and am still looking for it, and to that end only my heart is bent.”

In 1818 he was offered the possibility of earning money from the edited collection of his works. Heinrich immediately donated 35,000 francs to create a house for the poor, even though he had not yet received any of the money.

During his final years he returned to Neuhof. Despite being in his late 70s, he wanted to create another place for poverty stricken people. It was during this time that he wrote Swansong, which again described his philosophy of education.

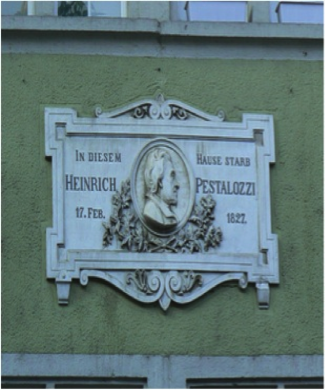

Heinrich died at the age of 80 and is buried in Birr, next to the school building at Neuhof.

Principles

Pestalozzi wrote on many subjects related to education – particularly social reform – but here we will mainly focus on some of his educational principles. Let’s start with his view of human development.

People can develop through the

natural state, social state and moral state

Heinrich believed that people went through three stages in their lives.

The Natural State

Pestalozzi saw children as divine, but he had reservations about Rousseau’s views on simply encouraging them to follow their nature.

He felt that, because of corrupting influences, their ego may take over and they would submit to animal nature. For example, they may become greedy, eat more than they need and selfishly exclude other people.

The Heinrich Pestalozzi site explains:

“In the natural state animal nature dominates; higher nature is dormant, like a seed. Curiosity, for example, is part of animal nature, but in higher nature it can develop into a genuine interest in truth.

“Indolence originates in the tendency to avoid discomfort, but at the same time it is the natural basis for impartiality.

“Theoretically there are two natural states – the unspoiled natural state and the spoiled natural state. One has to distinguish between these two: The unspoiled natural state can only be imagined.

“It is the state when we live completely in the moment and there is a perfect balance between everybody’s needs and the fulfilment of everybody’s needs. As in the Garden of Eden before the Fall.

“Only the spoiled natural state can really be experienced. When a human takes action to fulfil the needs he experiences in the unspoiled natural state, he cannot help being selfish, and in taking action spoils the unspoiled state.

“Sometimes a human does more than what is needed to satisfy his needs, for example, by becoming greedy and eating more than he needs.”

The Social State

At a certain point, human beings progress to the social state. Building a society enables them to live and work together. This produces great benefits – such as certain rights – but it also brings responsibilities.

This balance of rights and responsibilities is embodied in laws and established institutions, such as financial, social and other agreements. The Heinrich Pestalozzi site says:

“Entry into society does not prevent the natural egoism of the individual; society only restricts it and thus protects people from its negative effects.

“Out of egoism or selfishness people desire all those advantages, which can only be attained through society.

“Out of the same selfishness people want to avoid or sometimes refuse all the restrictions and burdens of society, which exist to make social advantages possible.

“Being part of society does not bring about inner harmony for the individual. As the need to be part of society is a selfish need, one remains selfish by continuing to be part of society.

“Thus, society as such can never guarantee the individual real fulfilment, but can always only set up a framework in which the individual can gain self-realisation.

“The individual will remain in contradiction with himself and will suffer from the contradictions that lie in the nature of society. This will go on until the individual realises that real fulfilment can be attained only by voluntarily giving up egotistic or selfish claims.

“In this way suffering the burdens of social life can make people realise the importance of living as moral individuals.”

The Moral State

“Higher nature is what lifts humans to a level above animals,” says the Heinrich Pestalozzi site.

“This higher nature consists of the ability to perceive truth, to show love, to believe in God, to listen to one’s own conscience, to do justice, to develop a sense of beauty, to see and realise higher values, to be creative, to act in freedom, to bear responsibility, to overcome one’s own egoism, to build a social life, to act with common sense, to strive for self-perfection.

“Pestalozzi often calls this higher nature the ‘inner’, ‘spiritual’, ‘moral’ or ‘divine’ nature.

“A moral person realises that he has to fulfil a life-task – attaining his own perfection.

“This can only be achieved by the renunciation of selfishness and by the development of the moral powers or the powers of the heart – love, trust, gratitude, public-spiritedness, an eye for beauty, responsibility, creativity, religiousness, doing good of one’s own free will.

“Through the realisation of morality we transform ourselves into a better form of ourselves and therefore become truly ‘free’.

“The contradictions which are felt in the spoilt natural state and in the social state can only be solved by the attainment of individual morality.”

Pestalozzi believed the goal of education was to enable people to achieve what he called their moral state. Let’s explore a second principle at the heart of his work.

People can have inner powers that can develop

by learning through the heart, head and hands

Heinrich believed that every child had inner powers – certain unique strengths. Like many great educators, he felt the first step was to engage a person’s heart.

He felt this was relatively simple, however, providing you followed the child’s interests – what they wanted to reach out and learn. The key was to follow their aspirations and help them to master certain skills.

He wrote in Swansong:

“Man is also driven by the nature of each of these powers within himself, to use them.

“The eye wants to see, they ear wants to hear, the foot wants to walk and the hand wants to seize. But in the same way, the heart wants to believe and love.

“The mind wants to think. In every gift of human nature lies an urge to rise from the state of inactivity and lack of dexterity to that of a trained force which, if left untrained, lies within us like a seed of strength and not as strength itself.”

The educator can enable a person learn through:

The heart – to explore what they want to learn and also develop their moral qualities, such as helping other people.

The head – to intellectually understand objects, concepts and experiences.

The hand – to learn the craft of doing good work and also develop their physical skills.

The Heinrich Pestalozzi site explains:

“Nature has given each child particular natural powers and faculties which help lead it towards moral conduct. They make it tend to overcome its selfishness and turn towards its fellow human beings.

“Pestalozzi calls this natural social instinct ‘goodwill’ … Out of this will gradually develop – if the formative education is good – the basic moral emotions of love, trust and gratitude, on which all further moral-religious powers are based.

“In addition to these ‘powers of the heart’, intellectual and manual skills must also be developed.

“However heart, head and hand must each develop according to their own natural laws. The educator must get to know these laws and educate according to them.

“‘Conformity with nature’ is Pestalozzi’s supreme demand on education. Only education which follows the laws of nature can truly be called ‘education’.

“Any influence on a human which is not in accordance with nature is not fit to be called education.”

People learn best if their teachers embody love

People are then more likely to develop in a state of composure.

Children learn best from good models. They need educators who embody love for the child and their potential.

Such educators create an environment in which learners feel respected and able to explore. The children then feel at ease and grow in an atmosphere of ‘composure’ – which Pestalozzi believed was essential for true development. The Heinrich Pestalozzi site says:

“The powers of the heart can never be activated by pressure, coercion or compulsion, but only by the emotional, mental or spiritual life of the educator.

“Love in the child can only be evoked by love for the child. Trust only develops if the educator shows trust in the child.

“Respect for life, religious faith, affection towards all creatures – all can only be brought about in the child if it feels these attitudes in the adult. For this reason the inner life of the educator is fateful for the moral development of the child.

“According to Pestalozzi, a human develops his humaneness only face to face, only heart to heart – for example only through the experience of being loved can a child learn to love.

“For Pestalozzi formative education is always a personal process and it is the most important skill of the teacher to be able to be aware of each child’s individuality and to respond to its emotions lovingly.

“Pestalozzi believes that the moral development of the child is only possible in the basic mood of composure.

“This state of inner composure develops in the child on the one hand through the above-mentioned satisfaction of its needs (but not the fulfilment of its wishes) and on the other hand if the teachers radiate loving calmness.

“In this atmosphere of composure and of acceptance by fellow human beings, a ‘moral mood of temper’ develops in the soul of the child.

“The child is willing to share with others, to help others and to do them favours. Thus the powers of the heart develop.”

People learn through the senses:

first the experience, then the word

Pestalozzi believed that sense perception was the basis of all real education. After all, that is the way that human beings learn.

He rebelled against the prevailing approach of the time that forced children to learn by rote and recite facts which had little relevance to their lives.

Learning should be real, relevant and rewarding. It should go from the concrete to the concept, not the other way round.

There is an excellent explanation of Heinrich’s views on the State University web site, which says:

“Pestalozzi believed that education should encourage people to follow the natural way that human beings learn.

“The method rested on two major premises: (1) children need an emotionally secure environment as the setting for successful learning; and (2) instruction should follow the generalized process of human conceptualization that begins with sensation.

“Emphasizing sensory learning, the special method used the Anschauung principle, a process that involved forming clear concepts from sense impressions.

“Pestalozzi designed object lessons in which children, guided by teachers, examined the form (shape), number (quantity and weight) of objects, and named them after direct experience with them.

“Object teaching was the most popular and widely adopted element of Pestalozzianism.

“Pestalozzi’s object lessons and emphasis on sense experience encouraged the entry of natural science and geography, two hitherto neglected areas, into the elementary school curriculum.

“On guided field trips, children explored the surrounding countryside, observing the local natural environment, topography, and economy.”

Heinrich’s approach strongly influenced many educators who later focused on ‘learning by doing’. You can find the complete State University article at:

People can only develop their inner powers by action

and are then more likely to reach the moral state

Pestalozzi’s view is simple: you learn things by doing them. You pick something you want to learn – then develop by continual practice. Certainly this is obvious if you want to learn a skill in art, language or mathematics.

Maria Montessori, for example, pointed out that children love to repeat things until they have satisfied their inner goal. Repetition is the key to achieving personal mastery.

Heinrich encouraged people to follow this approach towards achieving the moral state. If you want to learn generosity, for example, you do it by being generous.

You develop moral qualities by actually living them – rather than simply talking. Looking at each person’s strengths and potential moral qualities, he wrote:

“Essentially each of these individual powers develops naturally only by the simple means of using it.”

The Heinrich Pestalozzi site explains this in more detail by saying:

“Only by actually thinking, (can) the power of thought is developed, and only by actually imagining, the powers of imagination get developed.

“The same applies to the powers of art; only by using it does the hand become skilled, only by strenuous effort does the body get stronger.

“And finally the same applies to moral powers; love only develops by the act of loving and not by talking about love.

“Naturally the simple question arises: how does real ability come about? The answer is just as simple: solely through persistent practice, which means through fresh repetition that is varied and imaginative, until proficiency (the ability) is acquired.

“The success of a lesson depends – viewed as a whole – on two didactic measures: on the one hand material must be gone through in a manner that makes it clear for the children and is deliberately experience-oriented; on the other hand all skills must be persistently practised in a way that is suitable for children.”

Practice

So what have been the effects of Pestalozzi’s work? He inspired many future educators, such as Friedrich Froebel and Maria Montessori. Building on his ideas about learning through the senses, both designed special materials for helping children to learn.

Pestalozzi’s philosophy is also believed to have strongly influenced John Dewey, who is seen as the founder of learning by doing.

But it was actually William MacLure, a philanthropist and social innovator, and Henry Barnard, the first U.S. Commissioner of Education, who introduced the ideas into America in the early 1800s.

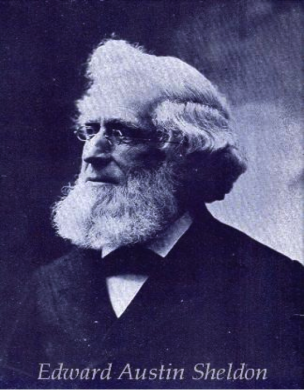

These were later put into practice on a grander scale by Edward Austin Sheldon at the Oswego School in New York. Sheldon was a pioneer in his own right, constantly seeking to bring learning to life.

Visiting a school in Toronto, he was impressed by how the children played an active role in their own learning. The State University site says:

“There, teachers based lessons not on recitation and memorization, but on pictures, charts, and other objects, a teaching technique credited to Swiss educator, Johann Pestalozzi.

“Many people saw shades of Pestalozzi himself in Sheldon’s life and work – both loved children, worked for the benefit of the poor, and maintained the courage of their convictions in reforming education.

“Pestalozzi developed object training out of necessity; he used field trips and actual objects as teaching tools because his students were poor and his school was inadequately funded.

“This active learning style was child-centered and engaged total sensory learning.

“Pestalozzi’s belief in nurturing the natural and orderly development of the mind struck Sheldon so strongly that ‘he became a Pestalozzian overnight’.”

Sheldon promptly introduced the approach at the Oswego School in New York. In particular, he focused on the object approach, enabling children to learn through their senses. This proved successful and became known as the Oswego Method.

“The impact of the Oswego (Normal) Training School cannot be overstated,” says the State University site.

“Teachers trained at Oswego fanned out across the country, beginning a revolution in classroom instruction.

“The majority of Oswego’s early graduates taught in elementary and even normal schools outside of the state of New York, often in the growing pioneer West.

“An Oswego graduate, Sheldon’s daughter Mary followed in her father’s footsteps; she became a professor of history at Stanford University and was well-known for her work in developing historical teaching methods.

“Mary and other Oswego-trained teachers helped to transform not only the subject matter and the methods of formal education, but also the spirit of education.

“Sheldon’s graduates took his object-training vision across the country and around the world. Oswego State Normal and Training School became synonymous with object training; many normal schools taught the Oswego method for years to come.”

You can read the complete piece at:

Heinrich believed that each of us act as models. Children learn from what we do, rather than what we say. He believed in the concept of resonance.

The feelings that live in our hearts are transmitted to others. Parents and teachers who embody love will enable children to develop their inner powers and fulfil their potential. He said:

“What lives in the souls of parents and teachers sets vibrating a corresponding chord in the child’s soul.”

You can find out much more about Heinrich’s work at the following site:

Leave a Reply