In the video above Maureen Moore provides an introduction to counselling. You can find more videos on this theme on the Counselling Channel.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC90Kade5cJKnh-eiMgjASIA

So how can a counsellor help? People like to feel in control. They like to be able to shape their future lives, but sometimes they encounter difficulties that take them off-track.

People are often able to resolve these challenges by themselves, with the help of friends or by using other resources.

On some occasions, however, a person may suffer a setback that proves hard to overcome.

This may involve bereavement, job loss, accident, illness, relationship breakdown, loss of direction or other difficult experience.

The person wants to regain their sense of control; but they may not know how to take this step. Sometimes on these occasions they may choose to get help from a counsellor.

Today many people use different kinds of counselling services. These can range from getting help with personal issues or dealing with practical problems, such as overcoming debt, or managing aspects of their professional life.

There are, of course, different views about the value of counselling.

Many see it as an important support mechanism for those who have experienced a trauma, loss or other setback.

Others see less value in the process and argue that it can foster a culture of dependency in society. Like any method, however, it can be used or abused.

One view is that, as people started moving away from their community roots, counsellors and therapists fulfilled a need previously met by the local priests and professionals.

People in the helping professions began taking the role of ‘secular priests’.

Many of these people were caring and extremely professional, but some were charlatans. Hence the need for formal training and, in some cases, qualifications being required to do counselling.

Bearing this in mind, let’s return to the roots of the field.

Carl Rogers and Counselling

Carl Rogers is a name known to everybody who has done a counselling course. Today it is hard to realise how revolutionary his ideas were in the 1930s and 40s.

In those days the medical profession treated people with psychiatric difficulties as ‘patients’. The doctor saw the patient, made a diagnosis and prescribed a ‘treatment’.

Few sat down with a troubled person to encourage them to clarify their feelings, set goals and take responsibility for shaping their future.

Psychoanalysis was an option for the rich, but few people had the opportunity of basic counselling. He changed all that.

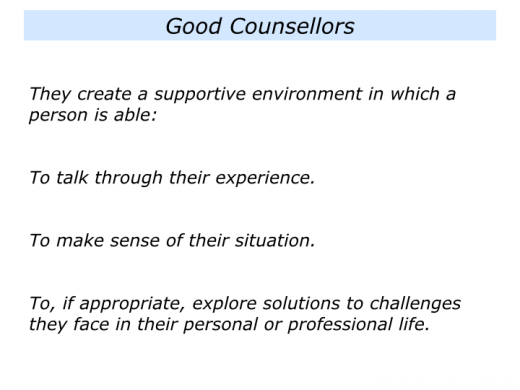

Carl outlined what he saw as the core conditions for building a good therapeutic relationship. He saw the helper’s role as:

To be ‘congruent’: to be genuine and honest with the client.

To show ‘empathy’: to understand and experience the world from the client’s point of view.

To have ‘unconditional positive regard’: to show respect and accept the person as they are, rather than be judgemental.

This may sound basic: but it was radical for an era in which the doctor, psychiatrist or other expert was expected to stay aloof.

Carl explained that, during in his counselling career, he met people who displayed many different symptoms. These were responses to what he called ‘problems of living’.

Considering his troubled clients, he said:

“(Everybody) has the same problem, in a sense – the problem of finding the right path, of acting according to one’s better inner nature …

“It seems to me that at bottom each person is asking: ‘Who am I, really? How can I get in touch with this real self, underlying all my surface behavior? How can I become myself?’”

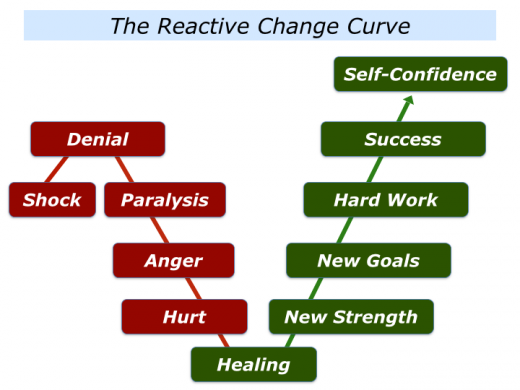

Counselling and the Change Curve

Veterans returning from the Second World War received a different welcome than their counterparts returning from the First World War.

It was recognised that, even if people showed few signs of disturbance, it could be useful to offer them the opportunity to talk through their experiences.

During the subsequent decades it became clear that people often went through certain stages after experiencing a trauma, loss or other setback. T

his became known as the Reactive Change Curve. The stages might include shock; denial; paralysis; anger; healing; gathering strength; setting new goals; hard work; success and a renewed sense of confidence.

The process was not linear and there could be frequent flashbacks. But people sometimes emerged stronger, wiser and able to meet new challenges.

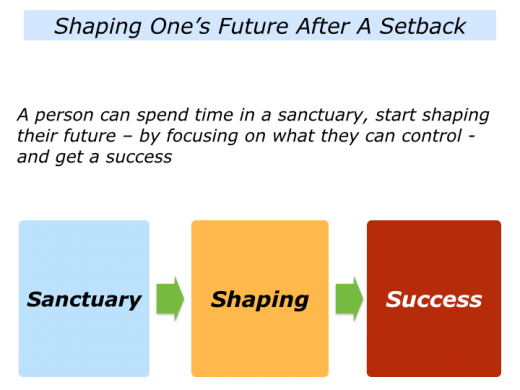

How to help a person through this process? Different people worked through the change curve in their own ways. But for many they needed:

To take time in a sanctuary.

To start shaping their future by focusing on what they could control.

To get a success.

Classic counselling focused on providing an environment in which people could express their feelings and eventually go through these stages.

The counsellor refrained from giving advice or direction. But in some circumstances it became apparent that people needed practical information.

This could be provided in a non-judgemental way and, done correctly, helped people to shape their futures. Let’s explore one example where lack of information led to death.

Chad Varah and the Samaritans

Chad was an Anglican clergyman who founded the Samaritans in 1953. Suicide was illegal at the time and he felt something could be done to help people in distress.

The official Samaritans site explains:

“The first funeral Chad Varah took as a curate prompted his lifelong commitment to suicide prevention and education.

“The funeral was for a 13-year-old girl who had taken her own life because she feared she was seriously ill; in fact she had started to menstruate.

“Chad vowed at her graveside to devote himself to helping other people overcome the sort of ignorance and isolation that had ultimately caused the young girl’s death.”

Chad was born in Lincolnshire and studied at Oxford before attending Lincoln Theological College.

He was ordained in 1936, then worked as curate in various parts of the UK before serving much of his working life in London.

Always daring to be different, he supplemented his early income by working as a children’s comic scriptwriter.

He helped to create Dan Dare, the spaceman, for The Eagle comic. The official Samaritans site continues:

“An early proponent of sex education, Chad Varah alerted society to the approach of the permissive society, usually associated with the 1960s, with an article in the Picture Post in 1952.

“Far more important to him than the outraged responses of conservative society were the 235 people who wrote in afterwards to bare their souls, 14 of whom showed signs of considering suicide.

“The opportunity to act on his earlier promise to help people in emotional need came in 1953 when Chad was appointed Rector at the Church of St Stephen Walbrook in the City of London.

“In the early 1950s, three suicides a day were officially recorded in Greater London; suicide was still an illegal act and sex education hardly existed.

“Chad advertised in the press for people to help – not as trained counsellors, but as ordinary human beings offering a listening ear and emotional support.”

“Inundated with offers of help, he opened the first drop-in centre where emotionally isolated and distressed people could go to find a sympathetic ear – and Samaritans was born.

“Chad continued to run Samaritans until 1987, thereafter remaining an active member of the organisation and retaining a watchful eye over it even after his retirement.

“The movement now has 202 branches in UK and Ireland, with 15,500 volunteers providing emotional support around the clock.

“Its international arm, Befrienders Worldwide, works in more than 40 countries.”

Samaritans found that ‘providing a listening ear’ could enable people to take more charge of their lives.

Certainly some might use it as a constant emotional crutch, but it was still worth it, even if it helped only one person to live longer.

Chad pioneering work created a caring framework. This enabled many people to help themselves and live more fulfilling lives.

You can discover more about the Samaritans at:

Counselling People Who Have

Had Traumatic Experiences

Veterans returning from the First World War were often expected to simply get on with their lives.

As mentioned earlier, some of those returning from the Second World War were given the opportunity to discuss their experiences.

Since then it is become common to offer this service to people recovering from traumatic experiences.

Such counsellors often have a certain kind of personality and skills.

Al Siebert was an expert on helping people to overcome adversity. Below is the advice he gave to those counselling War Veterans. As he says, such work should not be embarked upon lightly.

Counselling and Psychotherapy

Counselling shares some characteristics with psychotherapy, but there are also some differences. Let’s start with the similarities.

The person must choose to seek help.

The counsellor or therapist must communicate their approach and what they can and can’t offer during the sessions.

The person and counsellor or therapist can then making clear contracts about their work together.

The major difference is often around the second step.

Classic counselling emphasises the importance of encouraging a person to talk through their experience. The counsellor is to refrain from giving advice or direction.

As counselling approaches have developed, however, they have become more specialised in helping people to cope with particular situations.

A person dealing with debt, divorce, job loss or bereavement might actually want some practical advice.

(The grey area of providing guidance is compounded by some professional services adding the word ‘counselling’ to their title. Elements of Career Guidance, for example, may sometimes be described as Career Counselling.)

The key is that the person must voluntarily ask for help. If this is the case, it is okay for the counsellor to provide practical tools the person can use to shape their future.

In some schools of psychotherapy, however, the therapist is much more active.

The way they behave will depend on their particular approach: be it psychoanalytic, behavioural, humanistic, existential or whatever. This approach may have been made clear in the original contract, but it is sometimes a step beyond counselling.

The British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy offers the following view on what it sees as the differences and the grey areas.

http://www.bacp.co.uk/education/whatiscounselling.html

It is not possible to make a generally accepted distinction between counselling and psychotherapy. There are well founded traditions which use the terms interchangeably and others which distinguish between them.

If there are differences, then they relate more to the individual psychotherapist’s or counsellor’s training and interests and to the setting in which they work, rather than to any intrinsic difference in the two activities.

A psychotherapist working in a hospital is likely to be more concerned with severe psychological disorders than with the wider range of problems about which it is appropriate to consult a counsellor.

In private practice, however, a psychotherapist is more likely to accept clients whose need is less severe. Similarly, in private practice a counsellor’s work will overlap with that of a psychotherapist.

Those counsellors, however, who work for voluntary agencies or in educational settings such as schools and colleges usually concentrate more on the ‘everyday’ problems and difficulties of life than on the more severe psychological disorders.

Many are qualified to offer therapeutic work which in any other context would be called psychotherapy.

Counselling and The

Strengths Approach

Many people are now using elements of The Strengths Approach in counselling. Here is a brief look at how this works in practice.

Imagine that you are counselling somebody who is facing a difficult challenge.

One approach is to encourage them to clarify their experience and go through the change curve. At some point, however, a strengths coach may say something like the following to the person.

“Let’s learn from your positive history. Have you ever been in a similar situation in the past and managed it successfully?

“What did you do right? How can you follow these principles again in this specific situation?

“Let’s consider your strengths. How can you use your strengths and assets to tackle the challenge?

“How can you complement your strengths by getting other kinds of support?”

The person is encouraged to tap into their inner resources. Certainly they may also need to add some extra tools, but many people already have strengths and successful patterns. They can be helped to use these resources to take charge of shaping their future.

Here is another video from the Counselling Channel. In it counselling psychologist Dr. Anthony Crouch talks about how to help someone who is grieving.

This video contains an extract from a counselling session with a client who recently lost her mother. Dr Crouch explains how he approached the session.

Leave a Reply